15 Facts About Marriage In The Middle Ages

Marriage in the Middle Ages was a complex institution influenced by social, economic, and religious factors. It was a time when marriages were more than just personal unions; they were strategic alliances and social contracts. Understanding these historical nuances gives us a fascinating glimpse into the lives and challenges of medieval couples.

1. Most marriages were arranged—not chosen

In medieval times, marriage was less about love and more about alliances. Families often arranged marriages to strengthen social, economic, or political ties. A young girl’s parents would negotiate terms with the potential groom’s family, sometimes with the help of a matchmaker.

The bride and groom often had little say in the matter. This ensured that families could secure advantageous connections, although it sometimes meant personal desires were sacrificed. Such arrangements were accepted as the norm, reflecting the era’s communal values.

Vedi anche: 15 Ways Medieval Parents Chose Baby Names

2. Girls often married in their early teens

Marrying young was common in the Middle Ages, particularly for girls. It was not unusual for girls to be wed as early as twelve or thirteen. This practice was influenced by the belief that girls should marry soon after reaching puberty.

The early age of marriage was partly due to shorter life expectancies and the need to produce heirs quickly. While modern perspectives may view this critically, it was a practical aspect of medieval life. These unions were often arranged by families, prioritizing lineage and alliances over personal affection.

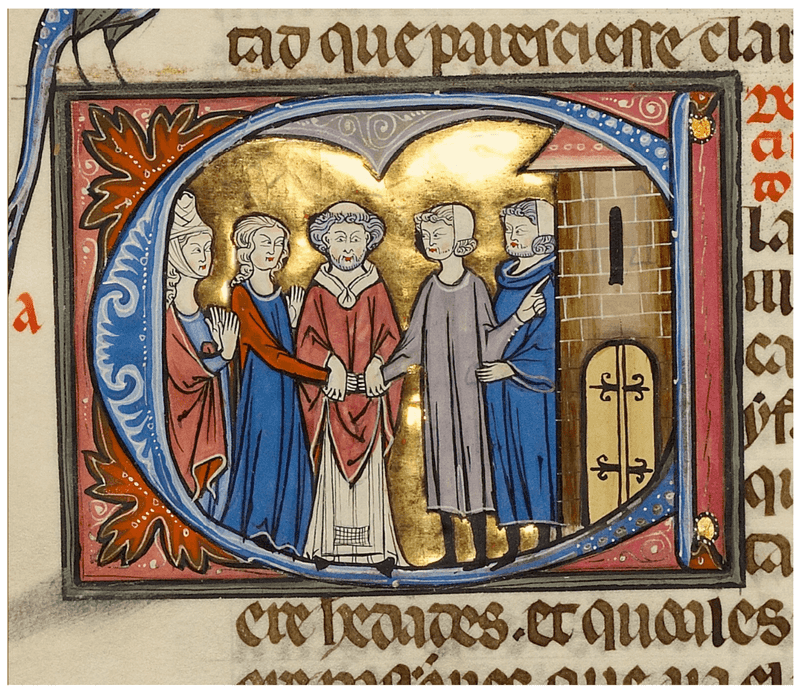

3. Consent was still legally required (in theory)

Legally, consent was a crucial element of marriage, even in the Middle Ages. Both parties were supposed to agree to the union, although in practice, this was often a formality. The church emphasized that consent should be mutual, but societal pressures and family dynamics could overshadow personal choice.

Medieval doctrine acknowledged the importance of mutual consent, yet young brides and grooms often felt compelled to agree due to family expectations. The gap between law and practice was significant, highlighting the complexities of medieval marital customs.

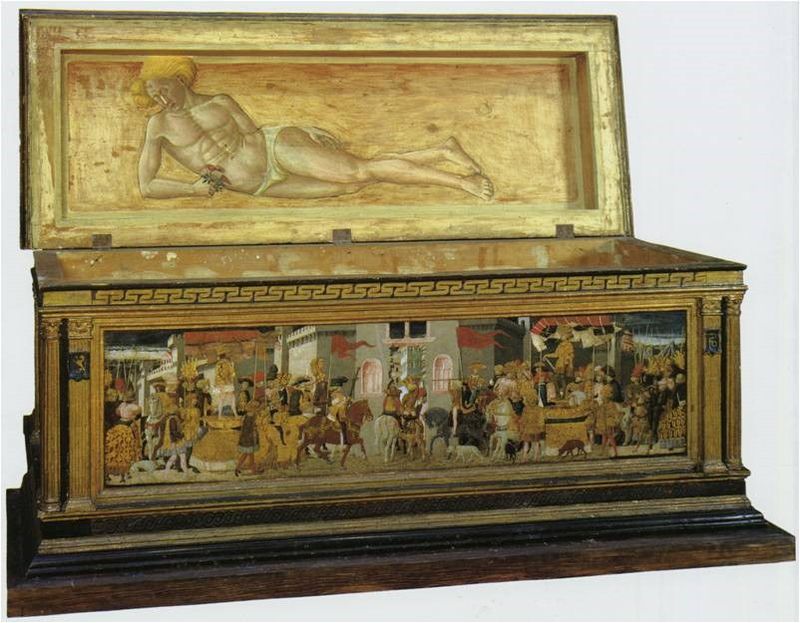

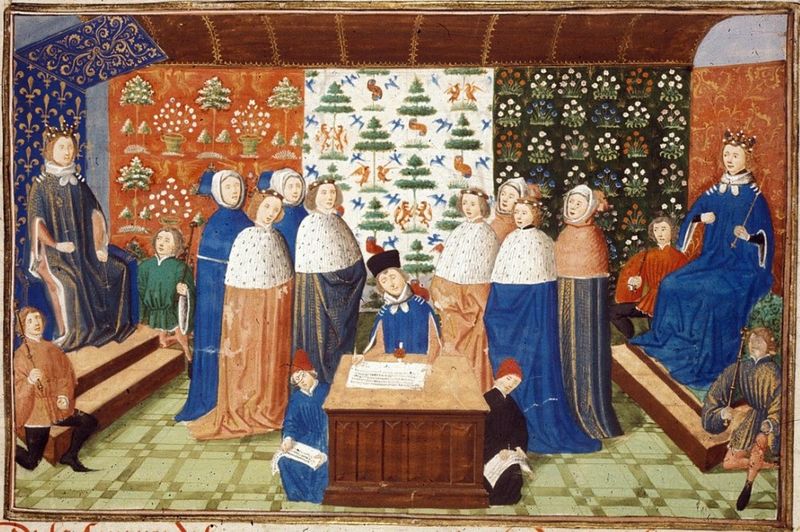

4. Marriage could be a business deal between families

Marriages in the Middle Ages were often akin to business transactions. Families treated the union as a strategic alliance, focusing on the benefits it would bring. Contracts were drawn up, detailing dowries, land exchanges, and mutual responsibilities.

Such arrangements were particularly common among the nobility, where the stakes were high. Despite the formal nature of these marriages, they were essential for maintaining or enhancing a family’s status and wealth. This pragmatic approach to marriage underscores the era’s focus on lineage and legacy.

5. Dowries were a major part of the negotiation

Dowries played a crucial role in medieval marriages. They were financial arrangements where the bride’s family provided money, property, or goods to the groom’s family. This was not merely a gift but a vital part of the marriage contract, symbolizing the bride’s contribution to her new household.

The size of a dowry could significantly influence a marriage’s desirability and was often a bargaining tool during negotiations. This custom highlights the economic dimensions of marriage in the Middle Ages, where love was secondary to financial security and family honor.

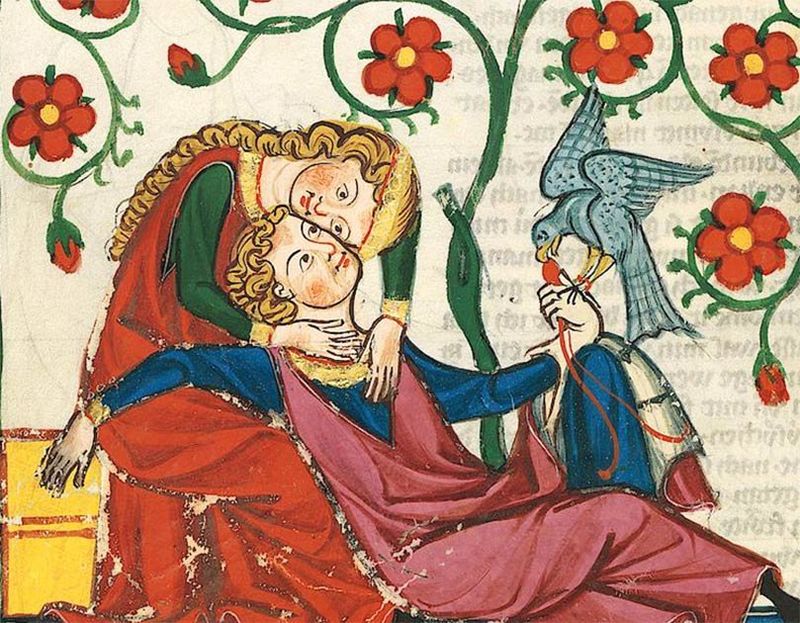

6. Love matches were rare and often discouraged

Romantic marriages were rare in the Middle Ages. Society prioritized alliances, so love matches were often viewed with suspicion or outright discouraged. Families believed that marriages should be strategic, not emotional. While love might develop over time, it was not the foundation for most unions.

Secret romances did occur, with tales of star-crossed lovers whispering in gardens. These stories inspired much of the medieval literature, showcasing the tension between duty and desire. The rarity of love matches speaks to the era’s rigid social norms and expectations.

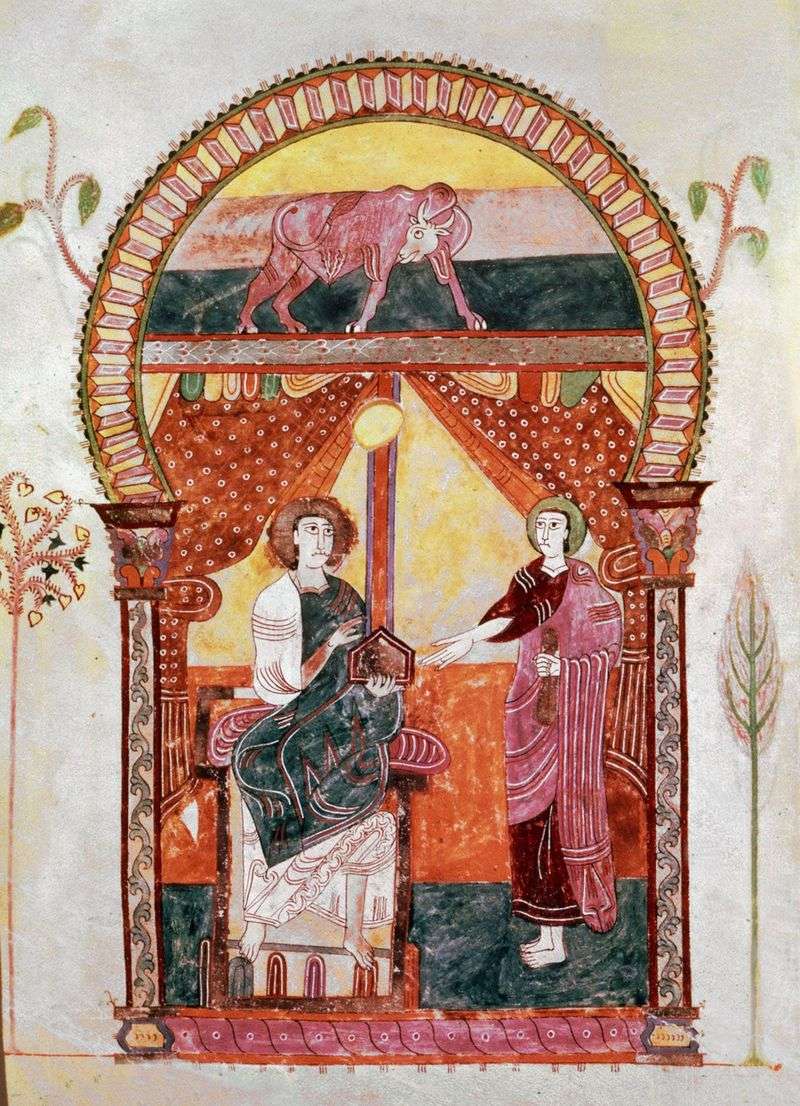

7. The church held ultimate authority over weddings

The church played a central role in medieval marriages, holding the ultimate authority over the sacrament of matrimony. Clergy officiated weddings, and ecclesiastical courts handled disputes and annulments. The church’s influence ensured that marriages adhered to religious doctrines, with ceremonies often held on church grounds. This spiritual oversight reinforced the idea that marriage was a sacred bond, overseen by divine authority. The church’s involvement extended to defining marital laws and practices, shaping medieval society’s views on marriage and family.

8. Noble marriages were often political alliances

Noble marriages were highly strategic, often serving as political alliances. These unions were arranged to consolidate power, secure borders, or forge alliances between kingdoms. The stakes were enormous, as these marriages could influence entire regions. Parents meticulously planned noble weddings, considering political ramifications over personal feelings.

Such alliances were crucial in maintaining peace and stability, reflecting the interconnectedness of medieval politics and matrimony. The grandeur of these weddings often mirrored their political significance, with elaborate ceremonies and celebrations.

9. Divorce was nearly impossible

Divorce in the Middle Ages was a rare and challenging process. The church viewed marriage as a lifelong commitment, rendering divorce nearly impossible. Annulments were the only option, granted under strict conditions, such as discovering pre-existing impediments. Couples seeking separation faced significant obstacles, as ecclesiastical courts handled such matters with caution.

The rarity of divorce highlights the era’s emphasis on marital permanence, where ending a marriage was seen as a failure to uphold sacred vows. This rigid stance reflects the church’s control over marital norms.

10. Widows sometimes had more freedom than wives

In an unexpected twist, widows often found more freedom than their married counterparts. Free from the direct control of a husband, widows could manage their own affairs, inherit property, and make decisions. This newfound autonomy allowed them to play significant roles in their communities.

While society still imposed restrictions, widows had the opportunity to influence their destinies more than when they were wives. This shift in status underscores the complex social dynamics of the Middle Ages, where widowhood, though accompanied by grief, offered a unique form of independence.

11. Weddings were simple, not lavish

Contrary to modern expectations, medieval weddings were often simple affairs. Lavish celebrations were reserved for nobility, while common folk opted for modest ceremonies. Weddings typically took place in local churches with only a few witnesses. The focus was on the sacrament rather than extravagance.

Simplicity extended to attire and festivities, emphasizing community over spectacle. This approach reflected the practical realities of medieval life, where resources were limited, and the sanctity of marriage was paramount. The simplicity of weddings highlights the era’s values and priorities.

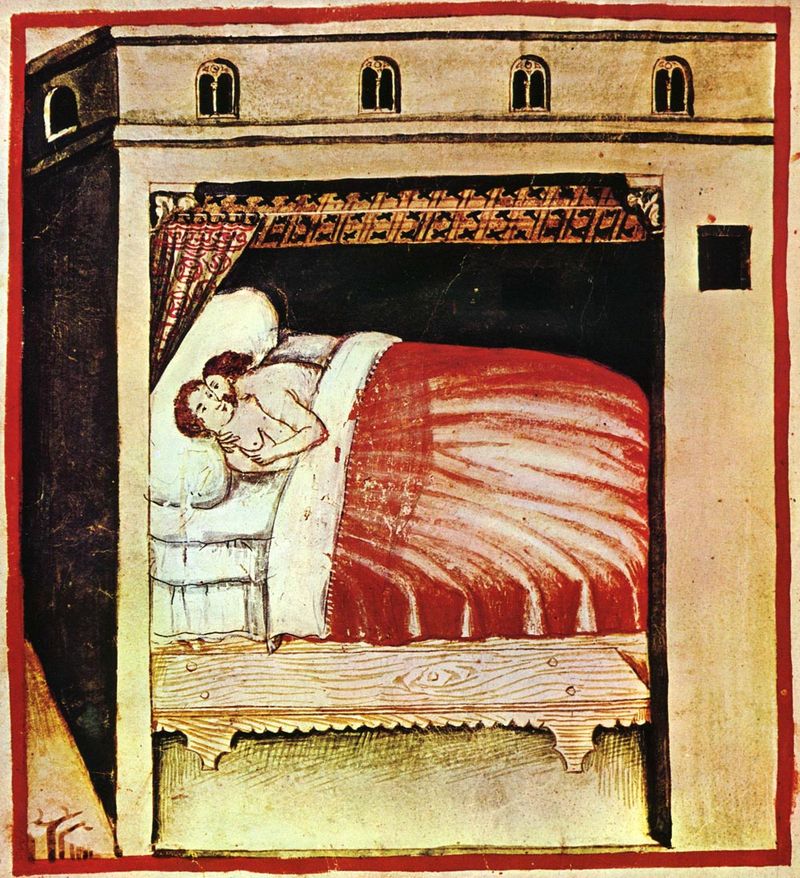

12. Proof of consummation was sometimes demanded

In some medieval communities, proving consummation was necessary to validate a marriage. Such proof often involved displaying bed linens or having witnesses. This practice, though intrusive by today’s standards, was rooted in ensuring legitimate heirs and cementing alliances.

Consummation marked the final seal of the marital contract, with communities sometimes participating in the validation process. While not universally practiced, this custom highlights the era’s preoccupation with lineage and legitimacy. The demand for proof underscores the social weight placed on marriage as a binding contract.

13. Second marriages were common due to high mortality

High mortality rates in the Middle Ages meant second marriages were not uncommon. Widowers and widows often remarried, driven by the need for companionship and economic stability, or to provide parental figures for children. The church permitted second marriages, recognizing the practical necessities of life. These unions, borne out of necessity rather than choice, reflect the harsh realities of medieval life.

The frequency of second marriages highlights the resilience and adaptability of individuals navigating personal loss and societal expectations. These remarriages were pragmatic, offering stability in uncertain times.

14. “Banns” had to be publicly announced

Before a marriage could proceed, the “banns” had to be announced publicly. This practice involved a priest declaring the couple’s intent to marry on several consecutive Sundays. The announcement allowed time for any objections based on legal or religious grounds. Public banns served as a form of social regulation, ensuring transparency and community oversight.

This practice was essential for maintaining order and preventing clandestine marriages. By making marital intentions known, communities could safeguard against unlawful unions. The tradition of banns underscores the communal nature of marriage in medieval society.

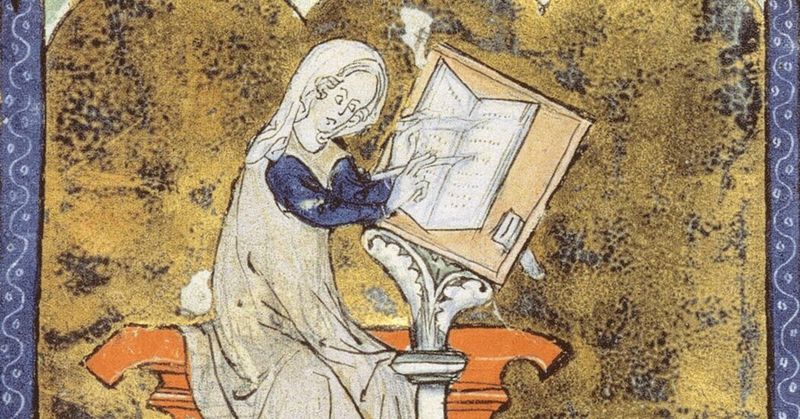

15. Marriage determined your legal and financial identity

In the Middle Ages, marriage significantly affected one’s legal and financial identity. Upon marriage, a woman’s legal rights were often subsumed under her husband’s authority, a concept known as coverture. This meant her property, earnings, and legal standing were largely controlled by her spouse. However, dowries and jointures provided some financial security.

Marriage was not just a personal milestone but a transformation of one’s public and private status. The legal ramifications of marriage reflect the era’s patriarchal structure, where marital status determined social standing and personal autonomy.